In a world of ubiquitous data and increasing analytical power, we mustn’t forget the power of stories and narrative in making sense of the world. Chris explores what the impact of this on understanding the student experience and the lessons for leaders.

How would you describe the experience of studying at your university to prospective students? Come up with 5 words or phrases that sum it up best. Take a moment to write them down.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

OK, next question; how do you know these are true? Where have these ideas come from?

My guess is that will be quite a complicated answer. Maybe you can point to some form of hard evidence behind some of these; results of surveys, TEF scores, general facts and figures.

But what about the ones where there is no direct measure? If you said something like “collaborative” or “challenging” there might be some data you can draw an indirect link to but I suspect there’s probably more going on than that: something less tangible and more subjective. Perhaps you’ve got it from things people have said to you, or events you’ve observed. Maybe it’s just a feeling.

So what can we rely on when it comes to making sense of the world? What’s “true”?

We can collect and analyse facts and data. But we can also listen to stories; those people tell us and those we tell ourselves.

I want to stand up for story and narrative as valid way to view the world.

A quick word about stories and narrative

Before we get into this, I should explain my key terms as “story” and “narrative” as we often use them interchangeably. I’m using the word “story” to mean a thing that is told, either internally or shared. It’s commonly a series of events tied together to create sense of a situation. “Narrative” refers to the meaning that we derive of the world by bringing one or more stories together. We can see a narrative as valid if we can also identify stories that back it up which can be a conscious or unconscious process.

It does get more complicated than that, though. A strong narrative understanding of a situation can lead to certain stories to be ignored if they don’t “fit”. Also, narratives can persist long after the original stories that formed them have been forgotten. This short story by Paulo Coelho about cats and monks illustrates this.

Right! Back to the action…

Stories and organisations

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea of scientific management, sometimes known as Taylorism, was popular in some quarters, mainly industry. It was the start of the boom in production line manufacturing and scientific management proposed analysing and perfecting workflows to increase economic efficiency and labour productivity.

At its simplest, the underlying assumption is that organisations are like machines; a series of inputs, processes and outputs and these can be fine-tuned to deliver maximum benefit to shareholders and owners.

This form of thinking began to fall out of favour in the years leading to the Second World War, although its more useful elements survive to this day where we have ever more complex organisations and problems to solve.

The reality is that organisations are social, especially in education; run, operated and experienced by humans. People engage with the organisation and their colleagues according to a complex mix of information and motivations that are difficult to identify and sometimes impossible to measure. Authors like David Boje, Yiannis Gabriel, Stefanie Reissner and others have been looking at this for 20 years.

To explain these seemingly competing philosophies, psychologist Jerome Bruner explored how we construct reality using 2 complementary modes of thought, one based on empirical evidence, logic and rationality, the other on interpretation of lived experience. If data is the bedrock of the first, then stories are fundamental to the second. Stories are what we use to create structure and meaning out of messy daily experience.

How might this look in education?

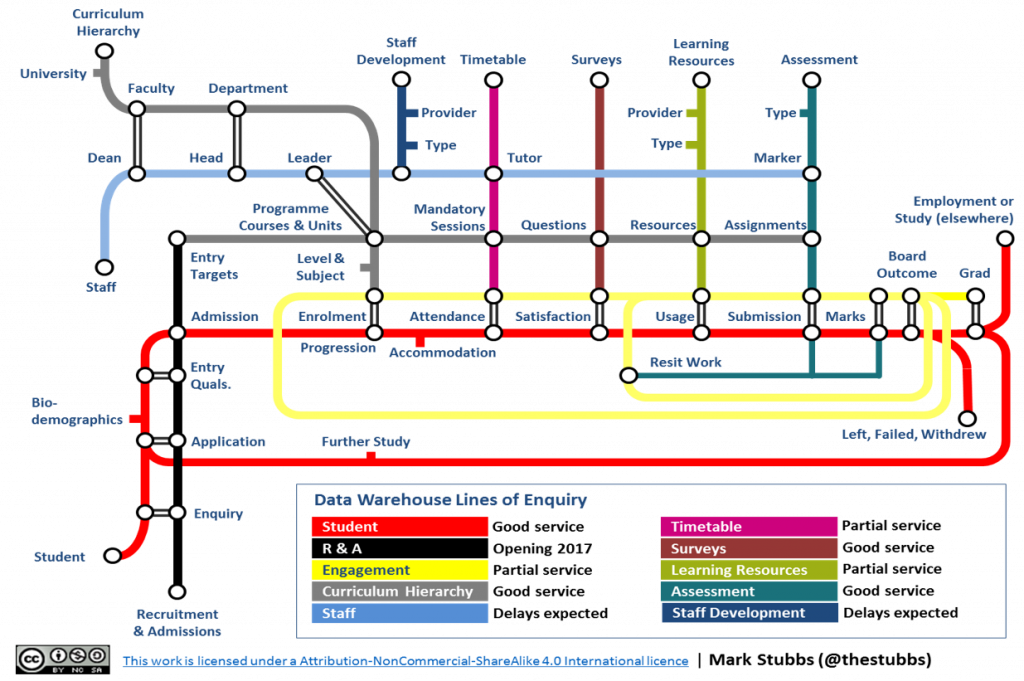

As students interact with systems and services during their education, there’s likely to be data generated in some form. This data map created by Mark Stubbs shows how detailed that picture can be for just one institution. Click the image for a larger version.

That data can be collected, collated and analysed to identify patterns. This is a powerful tool for the students but also for practitioners and leaders in those organisations. When operating at the scale of most higher education institutions it’s essential in planning services, allocating resources and responding early to problems.

Bruner’s argument is that if we focus purely on the data and the systems, like Taylorism tried to do, we ignore a huge part of the reality of how people learn work and live. Let’s take a deliberately extreme example…

It seems that on a fairly regular basis, a technology is proposed as a way measuring or improving students’ engagement with learning. A recent example was a headband that used “electroencephalography sensors” to monitor and record students’ brain activity as they studied. The argument is that it should be possible to see when someone is “switched on” to learning or when they are distracted. A teacher or student can gather actionable evidence to address any shortcomings. It needn’t be brainwaves. We’ve seen proposals for facial expression analysis and body motion capture for the same purpose.

What’s being measured here?

The problem here is a relatively simple use of data to try and measure something very complex. It mistakes “attention” for “engagement”? Attention is comparatively easy to measure. How long did you look at something; what items did you click on; how accurately did you answer a question?

Engagement on the other hand is much more complex and open to different interpretations. For example, if a student doesn’t appear to be logging onto the VLE on a regular basis, are they disengaged? Is a student who seems to be fully participating by the data properly engaged. And is it down to the university or the student to determine what engagement looks like?

Anthropologist Donna Lanclos has explored more deeply the complex behaviours of people engaging with learning via digital tools and platforms.

How do we come to understand engagement better? Well, I think it’s by listening to the students’ experiences and reflections and entering into a dialogue with them. And it’s through stories and the narratives that are built from them that we can do that most effectively.

The University of Gloucestershire approach to data analytics and students’ wellbeing shows how both modes of sense-making, data and narrative, can be brought together for to improve the student experience.

Aren’t stories too subjective?

The question of whether we can rely on stories to help us make decisions and run an organisation is a good one. 3 points:

- You shouldn’t try to run things based on stories alone, that would be irresponsible and bad governance. But you shouldn’t ignore them either. Stories are how navigate the world, whether we know we’re doing it or not.

- Every story is filtered to some degree, whatever form it takes. You don’t get ALL the information, just the bits that the storyteller thinks are relevant. Sometimes you can learn a lot from a story by looking at the negative space around the story; how someone has chosen to tell it, or indeed how they have chosen not to tell it.

- The field of data, machine learning, algorithms and so on isn’t immune from subjectivity and human influence. We still make decisions on what data to look at, what to ignore, how to present it and how to act on it based partly on a narrative understanding of the world. Criticisms of how algorithms are open to human bias are an example of the impact of this. With both data and stories, we need to acknowledge what we as the listener/observer bring to the table – we play an active part in the process.

Stories for empowerment

Another reason to engage with stories is what the act of storytelling does to relationships in organisations. They can be a powerful tool for building those relationships but also addressing imbalances of power and opportunity.

Patient Voices is a programme that has been running for many years in the field of healthcare. Health, like education, is a field where large amounts of data and information interact with people, often in emotionally charged situations. A traditional view of healthcare is that it is a service delivered to patients by experts. Patient Voices is digital storytelling initiative that sets out to redress the power imbalance, in their words by using:

“…reflective digital storytelling to unearth first-person stories that deliver compelling and motivating insight and drive organisational change, growth and success.” Source https://www.patientvoices.org.uk/

They work with patients and practitioners to collect and share personal, authentic stories about the experiences of illness, recovery or clinical care; reinserting the human voice into a system that can sometimes feel depersonalised.

In a similar vein, Dr Liz Austen at Sheffield Hallam University has been running a project to collect the stories of students from traditionally hard to reach groups. People from under-represented social and economic backgrounds can struggle to get their needs addressed in large organisations so this is an active step towards addressing this.

It’s because having your story heard is empowering, being listened to is different to being surveyed, or surveilled. Stories are as concerned with outliers as they are with lines of best fit.

Tips for leaders on using stories and narrative.

How to understand and improve the student experience through narrative and story:

- Actively look for where the stories and narrative already are in your organisation. We come across them in day to day conversations but you’ll also find them across social media, news articles or visible in much more subtle ways.

- Create space for conversation, storytelling (informal or otherwise) and listening. Storytelling takes time and is hard to do at scale so you need to create opportunities with patience.

- Find ways to share your own stories or amplify those of other people. Modelling this sort of behaviour is one way to encourage others to participate.

- Try to find the stories from the individuals and groups who don’t normally get heard in the mainstream. Use those individual or collective stories as a chance to start wider conversations.

- Look for instances where students’ and staff’s stories clash with the “official” narrative, or where the stories clash with the data. Even if you think the story is “wrong” as you see it, there’s a reason the story is there. These can be signs of inconsistencies and problems within the organisation giving you an opportunity to solve them.

- Use storytelling as a tool to influence change or encourage new behaviours. Data on its own is rarely persuasive unless people can see a narrative meaning in it.